Jeff's Got Balls

You could argue that Amazon may live in the future, interacting with technologies well before us mortals see them in the mainstream. However, as the media savant Marshall McLuhan noted, “the future of the future is the present.” And thus, we don’t have to speculate on the future to uncover what it holds for us who surround Amazon in the Emerald City. To visualize this future, we can take a walk to South Lake Union, where Amazon has recently built a $4 billion urban campus. Architecture is the expression of the values of those who build it. To understand an organization’s values, one needs only to examine their architecture.

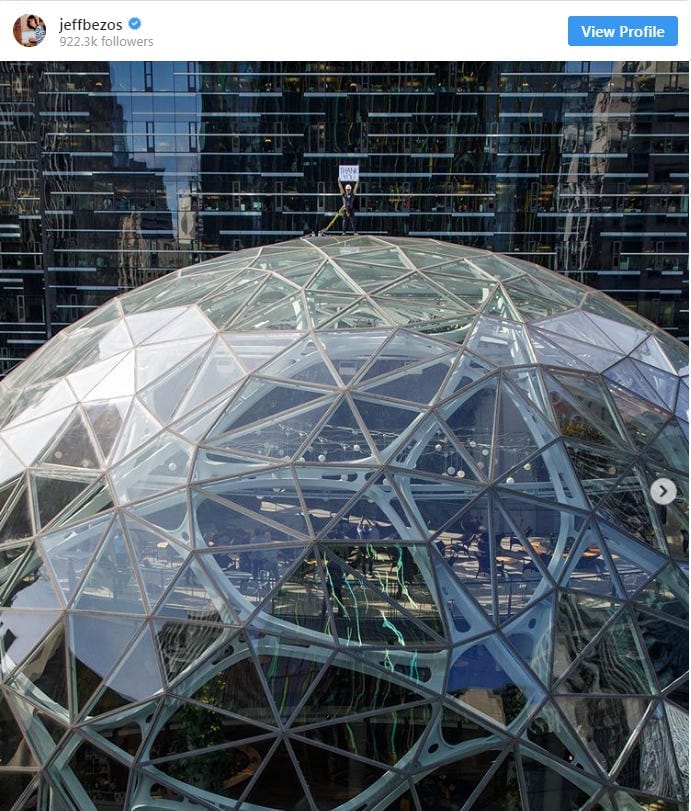

Perhaps, the most conspicuous architecture of the Amazon campus are “The Spheres.” Three connected balls that shelter a mechanically conditioned biome within, replete with exotic plants and exotic space. This building is noticeably unique in its geometry and technical sophistication. It solicits awe from passers-by and forms the crown jewel of Amazon’s urban campus. However, it is not merely a jewel, a treasure from the fortunes of technology. It is an iteration in the ancient art of power and control.

The project itself follows consistently within the control-forming and power-concentrating architectural methods of pre-Christian urban centers. At their core, a temple was found. Here, within the temple, capital ‘A’ architecture was born. As social critic Lewis Mumford wrote, “What we now call ‘monumental architecture’ is first of all the expression of power and that power exhibits itself in the form of costly building materials and of all the resources of art, as well as in a command of all manner of sacred adjuncts, great lions and bulls and eagles with whose mighty virtues the head of the state identifies his own frailer abilities. The purposes of this art was to produce respectful terror.”1

While the motifs of bulls, lions and eagles are omitted, the magical force of digitization oozes from this architecture. The motif of digital sophistication supplants the animalistic motifs of centuries past. Without digitization, Amazon would be nowhere, and thus, this project is a temple of digital complexity. A temple for which mortal humans may align with in the hopes of soliciting awe and respect from the their fellow urbanites. For, “the next best thing to successfully opposing a conqueror is to join his side and have a chance at some of the prospective booty.”2

While Amazon may live in the future, they also live in the past, falling for the same trap of power hungry kings who project awe through their architecture while consolidating a system of caste, social insider and social outsider. A digital-theistic order, impenetrable and indecipherable from the exterior, calculated and consumptive from within. The only thread that kept these kings in power was the concealment of knowledge, manufactured and privileged for the minority in order to exercise divine right over the populous. (Amazon holds about 10,008 patent grants and 1,097 trademarks.)3

If Amazon projects this architecture as totemic to the future. Their vision is, unreasonably technically complex, inaccessible, and private. In this future, technology comes at such a high cost, only a few can afford it. Technology is idolized over human compassion. Knowledge is commodified and guarded for commercial gain. Plants become rare, endangered, commodities to be showcased and displayed by the wealthy who can afford them. Immense amounts of energy are consumed to stabilize ecosystems that are inherently incompatible in nature, all for the outward expression of power and control.

While ancient kings solidified their power in the display of rare foreign commodities, the spheres appear as a colonial repository as well. They are full of “old world” and “new world” treasure, as codified by Amazon. In the age of biotechnics, ancient Sumerian winged bulls become a bland passé commodity in comparison to the showcase of a rare corpse flower. In the age of overwhelming environmental destruction, biology itself becomes a commodity of wealth and power. The spheres hold collections from Vietnam, Brazil, Sumatra, Central America, Singapore, South Africa, and Australia. It is a collection that embraces Rene Decartes’ call that man, “may be the masters and possessors of nature,” a call echoed by James Watt that, “nature can be conquered,” a call so destructive and maniacal that it may prove civilizationally disastrous. Employees of Amazon have recently recognized these contradictions, writing a letter demanding more transparency and environmental responsibility. (See letter signed by over 7,000 employees)4

No kingship is complete without a healthy dose of surveillance and submission, keeping the proletariat in line to serve the king’s mission. This was exposed within a NY Times article5 and a New York Post6 story on Amazon’s work culture. Author James Bloodworth wrote that, “People just peed in bottles because they lived in fear of being disciplined over ‘idle time’ and losing their jobs just because they needed the loo.” He wrote that the Amazon warehouse he was employed at in Staffordshire, UK “is like a prison, with airport-style security scanners where workers are checked and patted down in case they steal.” This prison-like functionality is troublesome. Within the walls of Amazon, employees are constantly monitored and coerced into robotic efficiency.7

As Amazon pours money into local Seattle politics8, we must ask, are the values of this company the same values we wish to imbue in our local city council? Consumptive, secretive, repressive and feudal. Do we value capital expansion over honesty and social responsibility? Are these the deities and king we wish to worship? The answers to these questions continue to play out in front of us.

Mumford, Lewis. The City in History. Hardcourt, Brace & World: New York, 1961.pg 65. ↩

Mumford, Lewis. The City in History. Hardcourt, Brace & World: New York, 1961. pg 52. ↩

https://medium.com/@amazonemployeesclimatejustice/public-letter-to-jeff-bezos-and-the-amazon-board-of-directors-82a8405f5e38 ↩

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/16/technology/inside-amazon-wrestling-big-ideas-in-a-bruising-workplace.html ↩

https://nypost.com/2018/04/16/amazon-warehouse-workers-pee-into-bottles-to-avoid-wasting-time-undercover-investigator/ ↩

https://www.theverge.com/2019/4/25/18516004/amazon-warehouse-fulfillment-centers-productivity-firing-terminations ↩

https://www.seattletimes.com/business/amazon/amazon-contributes-200000-to-seattle-chambers-political-action-committee/ ↩